From Nadis To Neurons - Yoga & Neuroscience

| Date :21-Sep-2025 |

By DR BHUSHAN KUMAR UPADHYAYA :

A

ncient Yogic texts describe

Nadis, subtle channels

through which Prana (lifeforce) flows. Modern neuroscience

maps communication lines of

energy flowing through the neurons, nerves and large-scale brain

networks. Both Nadis and neurons

are not identical literal equivalents, but they are powerful, complementary models that overlap in

function and effect - and contemporary research is beginning to

trace those overlaps.

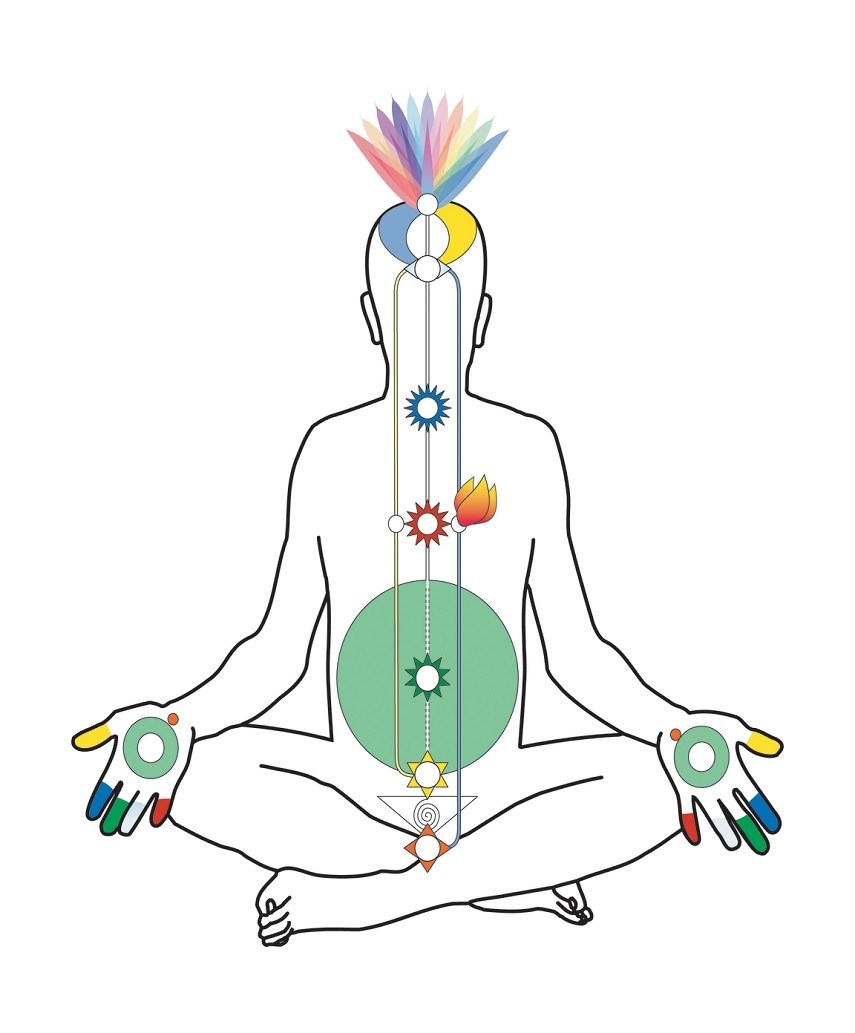

Yogic accounts (Siddha, Tantric

and Hatha traditions, and the

Swaravijñana lineage) describe

tens of thousands of Nadis with

three principal channels - Ida,

Pingala, and Sushumna - governing subtle flow and polarity.

Several comparative reviews and

critical studies have argued that

these classical descriptions show

structural and functional parallels

with the nervous system: Ida often

likened to parasympathetic

processes, Pingala to sympathetic

activity, and Sushumna to the

spinal axis or central conduits.

Swara and Pranayama practices

center on nostril dominance and

paced breathing - techniques that

classical teachers say influence

specific Nadis. Modern physiology

shows that controlled breathing

powerfully modulates autonomic

balance (sympathetic vs parasympathetic activity). Randomised and

controlled trials of alternate nostril

breathing and slow nostrilfocused practices report increases

in parasympathetic markers and

shifts in heart-rate variability

(HRV) consistent with vagal

(parasympathetic) activation. In

short: practices intended to influence Nadis measurably change

the activity of the autonomic nervous system.

If Nadis and Prana describe

inner states, contemporary neuroimaging shows long-term contemplative practice alters brain

networks that relate to attention,

interoception, and self-referential

thought. Experienced meditators

show changes in the Default Mode

Network, salience, and executive

networks - patterns consistent

with reduced mind-wandering

and improved self-regulation.

These network-level shifts align

with classical claims about transformed awareness when Prana is

regulated along the central

channel. Two useful takeaways

emerge. First, Nadis provide a

phenomenological, practice-oriented model: they tell practitioners how to work (breath, Bandha

attention) and what to expect

(shifts in calm, clarity, energy).

Second, neuroscience provides

measurable mechanisms (vagal

tone, HRV, network connectivity)

and clinical endpoints (reduced

anxiety, improved cognitive

resilience). Where yoga offers map

and method, science offers instruments and outcomes - and multiple studies now show the routes

overlap. For example, enhanced

vagal tone and HRV following

yogic breathing align with classical claims that nostril practice

shifts internal currents.

It’s important not to overreach.

Nadis are embedded in metaphysical systems (Chakras and

Kundalini ) that exceed current

empirical frameworks. Conversely,

reductionist claims that equate

Nadis strictly with specific nerves

or spinal tracts miss the symbolic,

experiential power of the yogic

model. Best practice: treat the two

as complementary languages -

one poetic and prescriptive, the

other analytic and measurable.

Researchers and practitioners

can benefit from dialogue: designing studies that translate yogic

protocols into testable neuroscience experiments (eg nostrilspecific breathing + HRV +

MRI)and letting clinical outcomes

inform practice refinement. Such

cross-translation preserves the

lived wisdom of Swaravijñana

while holding it to the clarifying

light of modern methods.

Nadis are not neurons, but they

are a prescient, practice-ready

map of physiology and experience. Modern science is catching

up by measuring how breath,

attention, and embodiment

change nervous-system function.

Together they form a richer story:

an ancient vocabulary pointing

toward discoveries that neuroscience is now quantifying.

(The writer is Former DG

Police & CG, Homeguards,

Maharashtra) ■