Tiananmen Square massacre: A tale of facts in blood, lies in ink

| Date :04-Jun-2023 |

By KARTIK LOKHANDE :

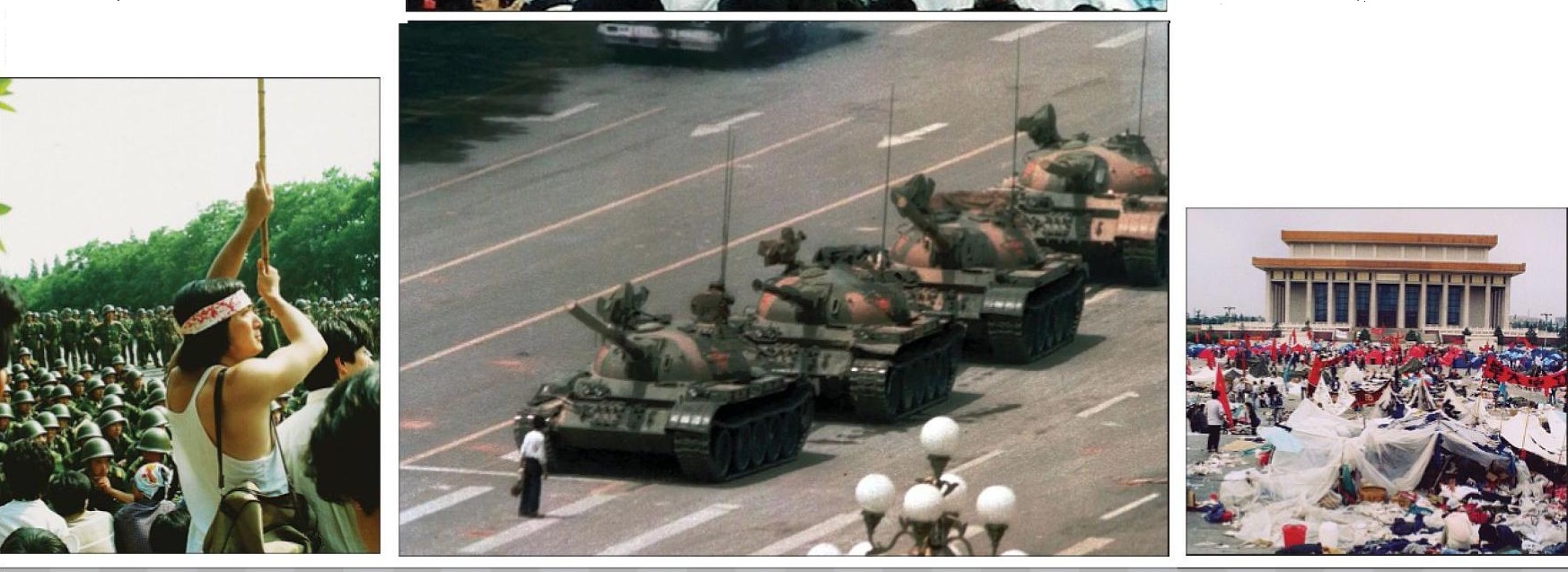

Much has changed in the world since

Communist China’s brutal crackdown on

pro-democracy protesters at Tiananmen Square

on June 3-4, 1989. However, in China, while the

citizens have been keeping the spirit of ‘Goddess

of Democracy’ alive in one way or the other, the

authoratarian regime has been busy tightening

its grip on public life to enforce ‘collective

amnesia’. But, as the recent happenings in

China show, people have not forgotten

Tiananmen Square massacre. The lies in ink

have failed to dilute the facts in blood. As the

ordinary Chinese citizens observe the 34th

anniversary of Tiananmen Square massacre,

‘The Hitavada’ provides a brief recounting of

the past in the light of the present context.

June 3-4, 1989.

These dates are etched in world’s collective

memory as days of bloodbath with specific

reference to Communist China. For, on these two

dates, Chinese government of the day unleased on

its own people - mostly students - the tanks, and

fired shots at them, to crush the 50-day long

pro-democracy protests. What had happened in

that spring and early summer 34 years ago, still

haunts the Communist China. For Chinese people

across the world, the anniversary of the Tinanmen

Square massacre is an occasion to rededicate

themselves to the cause of democracy in the

authoratarian rule in China.

Tinanmen Square ‘massacre’, which the successive Chinese authorities have been trying to sweep

under the carpet as an ‘incident’, brought to an end

the pro-democracy protests spurred by the death of

liberal leader Hu Yaobang on April 15, 1989. Hu

Yaobang was General Secretary of the Chinese

Communist Party (CCP) from 1982-87 till he was

forced to resign due to his views that did not gel well

with those of then Chinese towering figure Deng

Xiaoping. For it to be understood briefly, but in context, one has to go back to 1984-85 when Chinese

economy looked positive but concerns emerged.

Vijay Gokhale, former Ambassador of India to

China and an eyewitness to Tiananmen Square

happenings, has described the situation in China

very well in his masterly book Tiananmen Square: The

Making of a Protest.

He has observed in the book

that though the rural boom due to agriculture sector reforms was at its peak in China in 1984-85,

there were no additional gains in cities. He has also

recorded that there was ‘industrial overheating’ due

to Government spending in infrastructure, doubledigit inflation, and tightening of credit policies was

causing severe growth slump. Besides, fissures

emerged in CCP over proposed urban reforms.

Often, in western discourse on Tiananmen Square

happenings, the fissures within CCP are ignored

and focus is only on discontent among students.

The political fissures were, however, visible to the

public in 1986 when Wang Ruowang, who was

opposed to Deng Xiaoping’s methods, published an

essay titled ‘One Party Dictatorship can only lead to

Tyranny’. Another dissident Fang Lizhi, who was

backed by Hu Yaobang, proposed an academic conference to bring on record what he called ‘true story’ of Chinese dictator Mao’s purge of intellectuals

dating back to 1957. Such purges were regular during Mao’s regime to target the dissidents by

branding them as ‘rightists’ or ‘revisionists’ or

‘supporters of bourgeoise liberalisation’.

The idea of Fang Lizhi, who was at Chinese

University of Science and Technology at Heifei,

evoked a strong response from the authorities, who

decided to not proceed with the idea of electing university student bodies at his university. This started

the first spark leading to Tiananmen Square gradually. In 1986, students protested against this. In

fact, as per the records available, despite the best

efforts of the Communist China to erase those from

public memory, the student protests in 1986 spread

from Heifei to Shenzhen, Shanghai, Wuhan, and

Kunming too. Posters calling for ‘freedom’ and

‘democracy’ appeared at a couple of universities in

Shanghai.

Obviously unhappy, Deng Xiaoping dismissed Hu

Yaobang in January 1987.

Fang Lizhi was demoted

and Wang Ruowang was expelled. Deng tightened

his grip and brought Zhao Ziyang in picture as

General Secretary of CCP. Within two years, differences emerged between Zhao and Deng as the former was more liberal as compared to others.

Meanwhile, though the earlier student protests

were over, the Chinese authorities asked the

Ministry of Public Security to ‘establish units’ inside

key campuses to monitor student activity. State

Education Commission also was asked to ‘send work

teams to prevent big-character posters’. As per the

available records, Deng also was fed up of demonstrations being allowed by liberals and had even told

CCP Central Committee, “If there is a demonstration 365 days a year, nothing can be accomplished

and no foreign investment will come into this

country.”

While the situation was snowballing into a crisis,

Hu Yaobang’s death due to heart attack on April

15, 1989, unleashed the popular displeasure on to

the regime of the day. Soon, posters appeared in

praise of Hu Yaobang, and students gathered across

campuses to discuss his death, and wreaths were

laid for him. This, was the start of the Tiananmen

Square protests of 1989. It grew bigger as number

of students gathering at the Tiananmen Square rose

day after day, criticism about CCP and its leaders

surfaced. The seeds of economic problems and

curbs on people’s lives in Communist China bore the

bitter fruits of popular discontent. The students

demands reflected what ailed China at that time.

They demanded greater opportunities in education

and jobs, elimination of favouritism by way of ceasing extension of benefits to children of party cadres,

personal freedoms, and the Government to become

more responsive and sensitive to needs of citizens.

No Communist country tolerates dissent and

demands for freedoms, and China did not prove to

be an exception. Instead, as the protest extended for

almost 50 days and more and more people started

supporting the students not only at Tiananmen

Square in Beijing but also at other places including

Chengdu, Communist China set a bad example by

ordering military crackdown on own people. People

were mowed down by the tanks, shots were fired,

some were bayoneted on June 3-4.

As the videos of the time reveal, those injured in

firing by the Peoples Liberation Army troops were

carried to hospitals on benches as stretchers were

not available easily. Some ambulances carried the

injured to hospitals. Some of the students carried

their injured friends even on tricycles, with someone tailing or leading on bicycle. The ‘Statue of

Democracy’ made of styrofoam was installed during

the protests, but after June 4 crackdown, the statue

was turned into mangled remains, reflecting how

Communist China crushed democratic aspirations

of own people. In fact, one can understand the enormity of

the tragic loss from a reference in the book The

Tiananmen Papers. “The English-language section of China Radio International was the first

Chinese medium to announce the shocking

news to the world. At 6:25 A.M. on June 4, its

broadcast asked the world to remember the

‘most tragic events’ of June 3, in which it said

‘several thousand people, mostly innocent citizens’ had been killed by ‘heavily armed soldiers’.

It relayed eyewitness accounts of machine-gun

killings and of armored cars running over soldiers who dared to hesitate. It urged its listeners

to protest these horrible violations of human

rights and violent suppression of the people,”

reads a paragraph from the book. Obviously, for

this act of defiance of official diktat, the

Communist regime in China transferred the person in-charge of the English-language section

(who was the son of a Politburo member of

CCP) and investigated him. Besides, all the

employees of the section were forced to write

self-criticisms as is the Communist style.

Though the details came out in the

International knowledge to the extent that the

regime in China could not control initially, the

official exercise of suppression of facts by the

Chinese authorities began soon.

The authoratarian regime resorted to erasing collective

memory through expunging references or what

many call ‘cultural amnesia’ imposed by the

Government. In fact, a book on Tiananmen

massacre has been titled The People’s Republic of

Amnesia. Since then, there has been widespread

detention of journalists, artists, activists and

human rights lawyers ahead of the anniversary

of the Tiananmen Square massacre every year.

There has been an attempt to whitewash the

entire tragic chapter, with tightening of control

over publication and media and even digital

space. As the dissident Fang Lizhi has been

quoted as saying once, “Technique of forgetting

history, has been an important device of rule by

the Chinese Communists.”

But, from whatever material became available

to the other countries of the world, demands

have been growing for China to do full accounting of the massacre. More recently, on June 4,

2020, the Press Secretary of Trump-era White

House issued a Statement commemorating 31st

anniversary of Tiananmen Square massacre.

The statement minced no words and stated,

“The Chinese Communist Party’s slaughter of

unarmed Chinese civilians wasatragedy that

will not be forgotten. The United States calls on

China to honour the memory of those who lost

their lives and to provide a full accounting of

those who were killed, detained, or remain

missing in connection with the events

surrounding the Tiananmen Square massacre

on June 4, 1989.”

Democratic voices have been growing louder

even in Hong Kong, where the world recently

witnessed crackdown by the Communist China

on pro-democracy protesters. Within China

also, voices emerge for accountable and representative governance, freedom of speech,

assembly, religious beliefs, more open and transparent rights-respecting society.

As the world

saw, China was on the brink of ‘Tiananmen 2.0’

last year when tanks were on the streets once

again due to protests taking place against the

strict COVID-19 containment measures. There

was strict monitoring of sale of white cloth following what is known as echoes of ‘Sitong

Bridge protest’ in Beijing by one man in October

2022.

As per a report in The Independent (UK), the

banner put up by the lone protester read, “We

want food, not PCR tests. We want freedom, not

lockdowns. We want respect, not lies. We want

reform, not a Cultural Revolution. We want a

vote, not a leader. We want to be citizens, not

slaves.” He even called Xi Jinping, President of

China, as a ‘dictator and national traitor’. It

soon found echoes in other parts of China as

well as within Chinese community abroad. The

same newspaper reported thatagraffiti on the

walls of a public bathroom in Sichuan read,

“The spirit of 8964 will never be snuffed out.”

Here, ‘8964’ means the date of the Tiananmen

Square massacre with ‘89’ being the year 1989,

‘6’ being the month of June, and ‘4’ signifying

the date of China’s brutal crackdown against

the pro-democracy protesters.

It is but obvious even from the latest incidents

that the pro-democracy spirit in China is still

alive despite the authoratarian regime responding to dissent with censorship, surveillance,

arbitrary detentions, imprisonments, undermining of privacy rights, and attempts to erase

the memories of 1989 from the public mind.

Still, CCP has been continuing with its efforts to

portray 1989 massacre as ‘incident’ and justifying own stand. This is reflected in The Global

Times editorial of June 4, 2021 titled ‘1989 incident provides Chinese people immunity from

colour revolutions’. “If the incident 32 years

ago has any positive effect, that is, it has inoculated the Chinese people with a political vaccine,

helping us acquire immunity from being seriously misled. China underwent a ‘colour revolution’, but wasn’t brought down by it.

The leadership of the Communist Party of China has

saved the fate of the nation at a critical juncture,” it read.

It was the worst that the Tiananmen Square

had seen in China’s modern history. Lu Xun,

considered one of the greatest modern authors

of China, had probably anticipated that such

things might happen again when he wrote

after armed police had opened fire on demonstrators in Tiananmen Square in 1926 to crush

the protest against warlord Zhang Zuolin

accepting Japanese demands. Lu Xun had

prophetically written, “This is not the conclusion of an incident, but a new beginning. Lies

written in ink can never disguise facts written

in blood. All blood debts must be repaid in kind:

the longer the delay, the greater the interest.”

In 1989, after Tiananmen Square massacre,

the students in Chengdu had written on sheets

‘All blood debts must be repaid in blood’.

The book The Tiananmen Papers, published 12

years after 1989, makes a relevant mention at

one place, “The demand to be peacefully heard

wells up again and again from the Chinese people. As China develops, this is bound to be more

true rather than less. Dissenters within and

outside the regime will continue to insist on

being heard.

If there are no channels within

the system, they will go outside. The pressures

both between society and regime, and within

the regime cannot be handled without coming

to terms with the demands raised more than a

decade ago in Tiananmen Square.” Probably,

happenings in China in the past few years are

reflecting this sentiment in Chinese society.

In her wonderful and insightful book The

People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited

published in 2014, Louisa Lim has so aptly

summarised the situation of China with reference to Tiananmen Square incident: “The violent suppression of the 1989 movement was

not an anomaly. Its precedents were the May

4th Movement in 1919, the Tiananmen killings

that Lu Xun wrote about in 1926, followed by

the repression of mourning protests after the

death of Zhou Enlai in 1976, and the failed student movement of 1986–1987. Thus, Chinese

history loops endlessly in on itself in a Möbius

strip of crushed aspirations, cycling from one

generation to the next, propelled by the propensity to embrace amnesia.”

But, with rapid changes in the World

Economic Order, globalisation of technology

penetrating the toughest of the firewalls in one

way or the other and posing newer challenges

for the surveillance State, the virtues of democratic values of the free world will someday

breach the collective amnesia of the Chinese

people. Then shall come the true next revolution for the Chinese people, and from the bloodstains deep in the ground at Tiananmen Square

will rise the spirit of the ‘Goddess of

Democracy’. Then, the facts in blood will

triumph over lies in ink in case of China.